Progressive Education

Progressive schools are the legacy of a long and proud tradition of thoughtful school practice stretching back centuries.

The foundations of progressive education date back to The Enlightenment and progressive pedagogy crystallized into a movement in the early 20th century. Educators then experimented with the concepts espoused by John Dewey, Maria Montessori, and Rudolph Steiner, among others, in their schools.

The foundations of progressive education date back to The Enlightenment and progressive pedagogy crystallized into a movement in the early 20th century. Educators then experimented with the concepts espoused by John Dewey, Maria Montessori, and Rudolph Steiner, among others, in their schools.

As our understanding of how children learn best has evolved, we have come to know that a progressive curriculum is highly beneficial and effective for intellectual, emotional, and social development, especially during the foundational, elementary years.

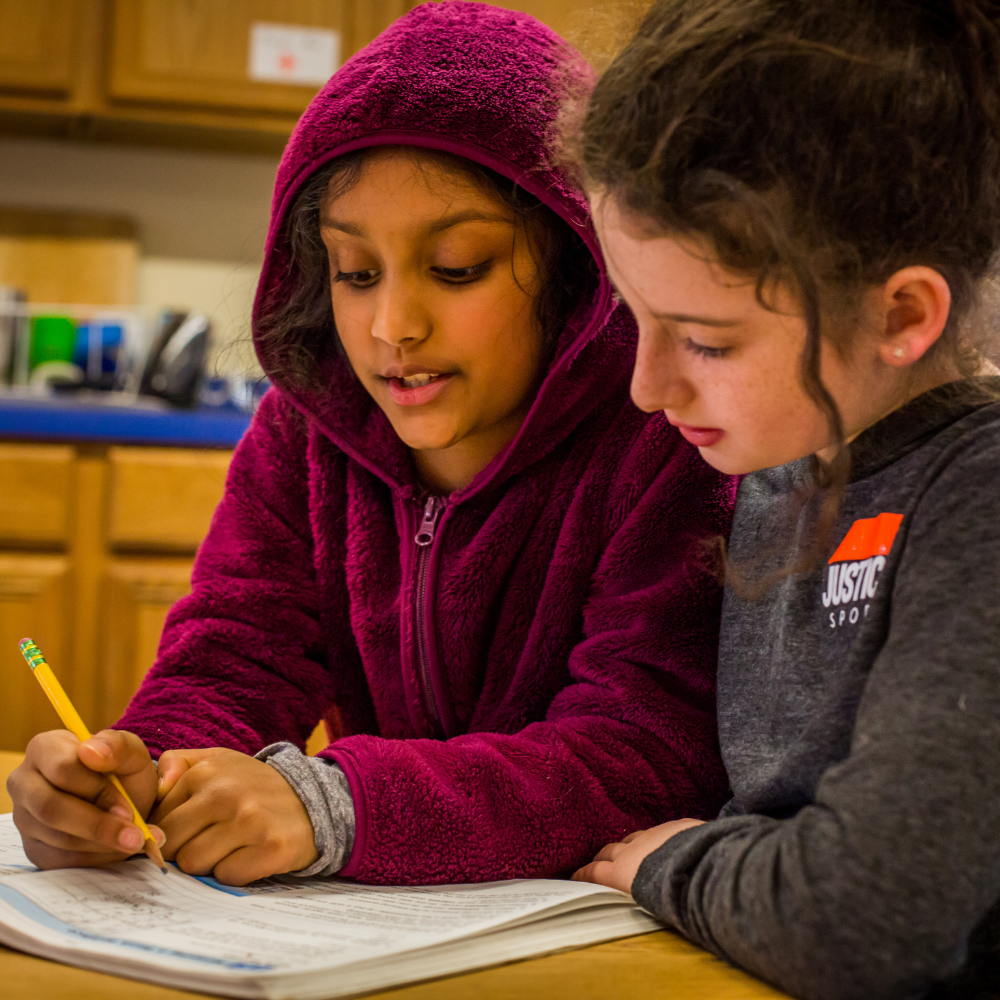

Simply put, progressive education is a philosophy that recognizes learning to be experiential, emergent, and collaborative. Progressive educators know that how lessons are taught is just as important as the lessons themselves, and that the most adept learners are those who are inspired to learn. Progressive education recognizes that learning should be authentic and enjoyable, and that the best teachers are those who encourage children to play an active role in their own development. Progressive teachers know the importance of helping children flourish both individually and as part of a group.

Simply put, progressive education is a philosophy that recognizes learning to be experiential, emergent, and collaborative. Progressive educators know that how lessons are taught is just as important as the lessons themselves, and that the most adept learners are those who are inspired to learn. Progressive education recognizes that learning should be authentic and enjoyable, and that the best teachers are those who encourage children to play an active role in their own development. Progressive teachers know the importance of helping children flourish both individually and as part of a group.

Teaching Children How to Think vs. What to Think

The progressive education model places children at the center of the learning process and emphasizes experiential learning over rote memorization; children should be taught how to think rather than what to think. Rather than simply doling out information, teachers dialogue with students, creating a dynamic and engaging learning environment that promotes a lifelong love of learning.

At the heart of progressive education is the process of learning by doing. This concept, known as experiential learning, allows students to learn by actively engaging in activities and hands-on projects. Applying what they are learning to real-life scenarios helps students fully grasp a subject and its applications as well as develop the skills they will need as adults. After all, the workplace is a collaborative environment that requires teamwork, critical thinking, creativity, and the ability to work independently. Progressive learning encourages students to reflect on their learning, follow their own questions, and engage in collaboration with peers and teachers, thus building their investigating, problem-solving, and communication skills.

What Are the Core Qualities of a Progressive School?

Experiential learning – A progressive classroom emphasizes “learning by doing” through hands-on projects and active, expeditionary learning. Instruction relates to the real world by providing context and meaning to students. It also allows students to construct their own understanding and knowledge of the world through experiences and reflecting on those experiences.

Emphasis on lifelong learning and skills – Teaching students how to be engaged, active, and responsible learners helps them develop the skills and habits of mind that make learning both accessible and fun. When students know themselves as learners, they become self-motivated, disciplined, open-minded, and flexible thinkers. This helps them cultivate a lifelong love of learning and develop key skills necessary for continued future success.

Interdisciplinary learning – Progressive classrooms use integrated curriculum so that students learn by forging connections between concepts and ideas across different disciplinary boundaries. When students apply the knowledge they have gained in one discipline to a different discipline, it deepens their understanding of a concept by looking at its real world applications. That is why there is minimal reliance on a single textbook for a subject in favor of varied learning resources.

Understanding as the goal of learning instead of rote knowledge – Traditional schools primarily focus on rote learning – the memorization of information based on repetition. While this allows students to quickly recall basic facts, it doesn’t provide a deep understanding of the information and how these facts relate to one another. Progressive education focuses on having a sound understanding of a subject so that students can apply the information to a variety of scenarios and form connections between new and previous knowledge. Students learn how to investigate, evaluate, analyze, remember, make comparisons, and communicate, giving them better problem solving and cognitive skills.

Collaborative and cooperative learning – By focusing on community, responsibility, and group participation, progressive classrooms help students develop the emotional intelligence and social skills they need to work in groups, enjoy healthy relationships, and to live fulfilling and successful lives.

Emphasis on problem solving and critical thinking – Progressive schools help students build higher-order skills (investigating, evaluating, problem-solving, and communicating) and encourage them to frequently reflect on their learning and follow their own questions so that they gradually fit knowledge into a meaningful whole. Students practice risk taking and teachers help them learn how to bounce back and learn from mistakes.

Teaching social responsibility and democracy – At progressive schools, moral development is not a separate section of the curriculum, but is intentionally interwoven in everything. Through community service and service learning projects, progressive educators value and actively teach students about democracy, encompassing freedom, responsibility, and participation.

Progressive Education at The School in Rose Valley

John Dewey, a renowned American educator and philosopher who founded the progressive education movement, felt that education should be a journey of experiences that build upon one another to help  students create and understand new experiences. He also felt that school activities and students’ lives should be connected for learning to truly be meaningful and memorable. Since 1929, this progressive pedagogy has has guided how we teach and learn at The School in Rose Valley. We encourage students to explore their academic and non-academic interests while providing them with a foundation for success both inside and outside of the classroom.

students create and understand new experiences. He also felt that school activities and students’ lives should be connected for learning to truly be meaningful and memorable. Since 1929, this progressive pedagogy has has guided how we teach and learn at The School in Rose Valley. We encourage students to explore their academic and non-academic interests while providing them with a foundation for success both inside and outside of the classroom.

Our curriculum connects heads, hands, and hearts. Literacy, math, science, social studies, languages, technology, service and partnership, art, music, woodshop, and unstructured play are interwoven in a challenging core of study and experience. This allows students to approach concepts and content from multiple perspectives at developmentally appropriate points, deepening conceptual understanding. Students build higher-order skills—investigating, evaluating, problem-solving, and communicating—in their ongoing collaboration with peers and teachers. Students reflect frequently on their learning and follow their own questions, gradually fitting knowledge into a meaningful whole.

From Fairhope to Rose Valley: A Brief History of SRV

In the early 1900s, the Progressive Education Association (PEA) greatly influenced 20th Century education in America and spread progressive education in American public schools. At its peak, PEA membership reached 10,000 (Graham, 1967). Harvard president Charles W. Eliot served as its first honorary president, followed by philosopher John Dewey. The PEA’s early founders included Marietta Johnson, principal at the Organic School in Fairhope, Alabama. The group struggled to regain its thought leadership position and collapsed in the mid-1950s amidst rising anti-progressive education sentiment.

The group adopted seven guiding tenets to drive growth and focus their organization, known as the Seven Principles of Progressive Education

- Freedom for children to develop naturally

- Interest as the motive of all work

- Teacher as guide, not taskmaster

- Change school recordkeeping to promote the scientific study of student development

- More attention to all that affects student physical development

- School and home cooperation in meeting the child’s natural interests and activities

- Progressive School as thought-leaders in educational movements

In 1929, Rose Valley residents sought the help of Dr. Carson Ryan at Swarthmore College to establish a school for their children. In addition to drafting incorporation papers, Ryan suggested the School hire Grace Rotzel, a teacher at the Organic School and a protegee of Marietta Johnson, as its first principal. Grace went on to lead the School for more than 30 years.

Fast forward to 2004. The School in Rose Valley, PA, celebrated its seventy-fifth anniversary by hosting a two-part national conference: Progressive Education in the 21st Century. Educators from progressive schools participated in the descriptive review of the child protocol. Discussions include the state of education, the PEA’s history, and subsequent forms, such as the Network of Progressive Educators. Alfie Kohn was the keynote speaker. Near the end of the conference, a group of seven educators rallied to a call-to-action to revive the Network of Progressive Educators, inactive since the early 1990s. As a result of the committee’s efforts, they formed the Progressive Education Network (PEN), and in 2009 was incorporated as a 501 (c) 3 charitable, non-profit organization (Little, 2013). The group hosted the organization’s first national conference in San Francisco in 2007, and conferences followed in DC, Chicago, and LA, with attendance numbers growing from 250 to 950.

The School in Rose Valley has an important place in the history of progressive education and its influence as a center for educational reform and the PEA tenets ring as true in our practice today as they did in the early 1900s.

Further Reading & Resources

Progressive Education: Why it's Hard to Beat, But Also Hard to Find by Alfie Kohn

Progressive Education Foundations

Emile by Jean Jaques Rousseau

Leonard & Gertrude and Enquiries into the Course of Nature in the Development of the Human Race by Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi

The Student’s Froebel: adapted from “Die Erziehung der Menschheit” by Friedrich Fröbel

Progressive Education Movement

Experience and Education John Dewey

The Montessori Method, Pedagogical Anthropology, The Advanced Montessori Method—Spontaneous Activity in Education and The Montessori Elementary Material by Maria Montessori

The Philosophy of Freedom by Rudolph Steiner

Deschooling Society by Ivan Illich

Democracy and Education, by John Dewey

I Learn from Children by Caroline Pratt

The Eight-Year Study: From Evaluative Research to a Demonstration Project Education Policy Analysis Archives

Talks on Pedagogics: An Outline of the Theory of Concentration And Other Writings by Francis Parker

The School in Rose Valley by Grace Rotzel

Progressive Education Continuum

Teaching as a Subversive Activity by Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner

Horace’s School and Horace’s Compromise by Ted Sizer

Keeping Wonder and Intellectual Hunger Alive by Bruce Shaw

Confessions of a Headmaster by Paul Cummins

Left Back: A Century of Battles over School Reform by Dianne Ravitch

The Power of Their Ideas by Deborah Meier

Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul by Avery Trade

Schooling Beyond Measure And Other Unorthodox Essays About Education

The Schools Our Children Deserve. Moving Beyond Traditional Classrooms and “Tougher Standards” by Alfie Kohn

Loving Learning by Tom Little and Katherine Ellison

Democratic Education in Practice: Inside the Mission Hill School byMatthew Knoester

Drive, When, and the Power of Regret by Daniel Pink

Creative Schools: The Grassroots Revolution that’s Transforming Education by Sir Ken Robinson

Dismantling Oppressive Structures

Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Friere

Savage Inequalities by Jonathan Kozol

Progressive Reading Education in America: Teaching Toward Social Justice 1st by Patrick Shannon

Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools and Sing a Rhythm, Dance a Blues: Education for the Liberation of Black and Brown Girls by Monique W. Morris

Cutting School: The Segrenomics of American Education by Noliwe Rooks

Troublemakers: Lessons in Freedom from Young Children at School by Carla Shalaby

The Skin That We Speak: Thoughts on Language and Culture in the Classroom edited by Lisa Delpit and Joanne Kilgour Dowdy